Editor’s Note: In 2021, we showcased the 1964 Cheney / Triumph “Cantilever Cub” of Graham Watson, whose father built the four-stroke race bike in the 1970s for 12-year-old Graham to compete against racers on non-British machinery.

Editor’s Note: In 2021, we showcased the 1964 Cheney / Triumph “Cantilever Cub” of Graham Watson, whose father built the four-stroke race bike in the 1970s for 12-year-old Graham to compete against racers on non-British machinery.

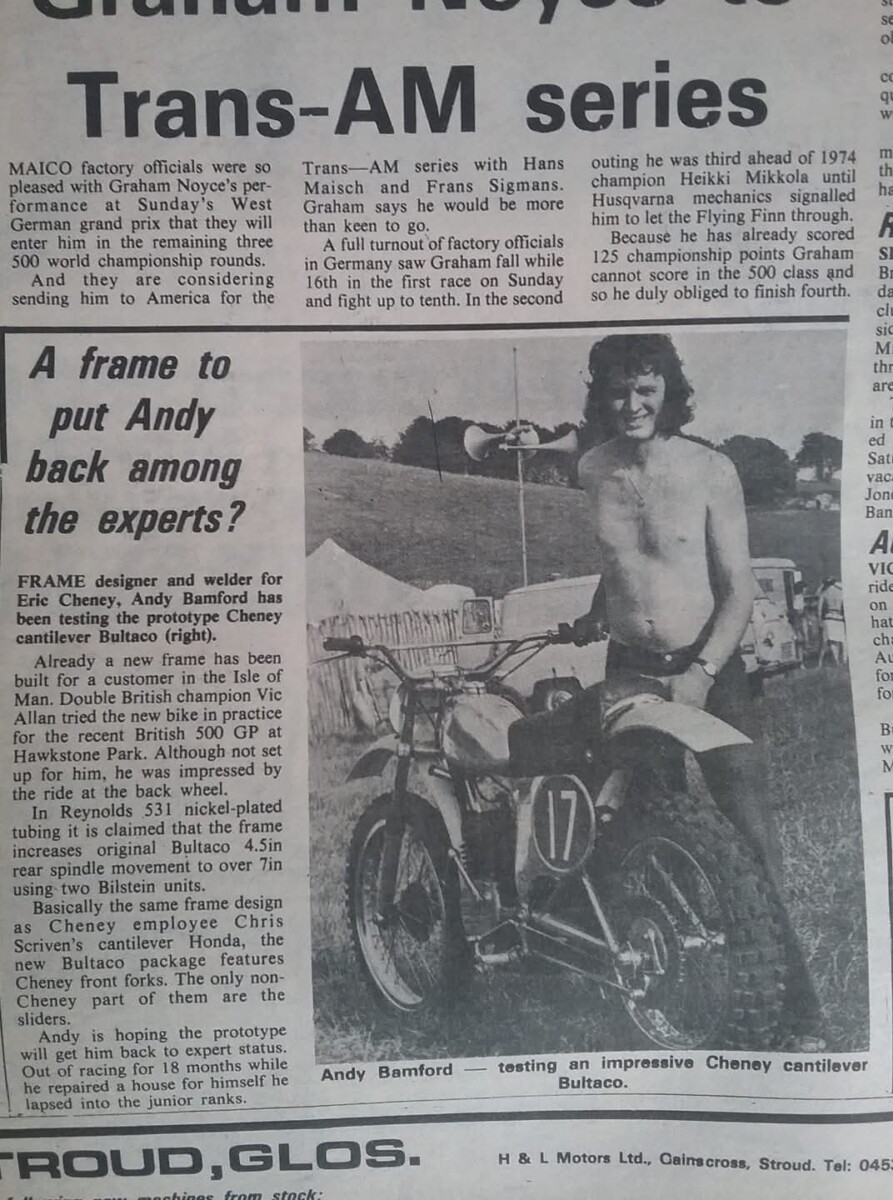

“In the back of my dad’s mind, he was still convinced he could build a British bike to compete with the growing input of Japanese and European bikes.” –Graham Watson

Graham has kept the Cub in good nick and continued to race it for many years. More recently, he’s been digging into the history of the innovative Cheney cantilever frame — a design that was well ahead of its time. Graham has put together an article about this important technological leap in the world of motocross, which came not from a major manufacturer, but the workshop of a quintessential British craftsman. We think you’ll enjoy it.

THE CHENEY CANTILEVER PROTOTYPE: AHEAD OF ITS TIME 🏁

Feature article for Classic Motocross and Vintage Engineering Enthusiasts

Period: Early 1970s – mid 1970s

Bike Featured: Cheney Cantilever Prototype Triumph Tiger Cub built by David Watson

Photography: Various (author’s archive and classic MX collections)

Contact: Graham Watson (@graham.watson.514)

INTRODUCTION

Few machines capture the spirit of British motocross innovation quite like the Cheney Cantilever Prototype. Designed at a time when motocross was rapidly evolving, it represented the leap into the era of long-travel suspension and advanced frame geometry.

This article explores how the Cheney Cantilever came to be — the engineering breakthroughs, the overlooked details, and the remarkable foresight of those who built and refined it.

PROLOGUE

I had the privilege of having a great father who, over fifty years ago, saw this remarkable frame and immediately recognised just how far ahead of its time it was. The engineering behind it was so advanced that even then, he could see what many others missed — the future of motocross frame design taking shape before their eyes.

After more than five decades of owning and researching my Cheney Cantilever, I’ve gathered notes, stories, and first-hand details that, in my opinion, deserve to be remembered. This isn’t an official Cheney Engineering publication. It’s the result of my own long-term investigation and personal research, based on technical records, period information, and my own experience of living with and studying the bike for decades.

I’ve never visited Cheney Engineering myself, but I did have a quick conversation with Simon Cheney around thirty years ago, which helped confirm several key details about the cantilever project. What follows is my effort to preserve a fascinating chapter of British motocross history — the story of one of the most advanced MX frames ever built.

THE EARLY 1970s — WHEN MOTOCROSS CHANGED FOREVER

Back in the early 1970s, motocross was developing at a blistering pace. Builders such as Cheney, Rickman, and CCM were all chasing the same goal — more suspension travel, better handling, and stronger yet lighter frames.

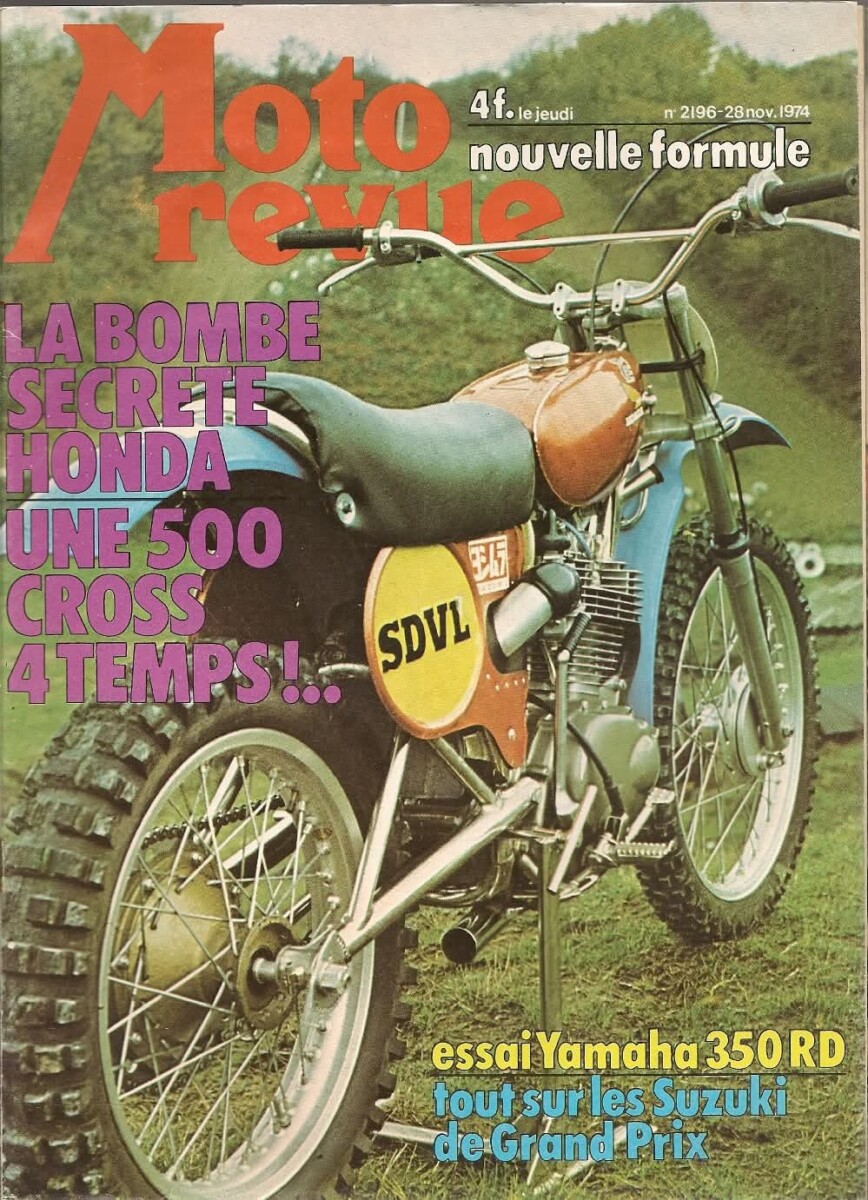

At the same time, the sport was being transformed by what became known as the Japanese invasion. Manufacturers like Yamaha, Suzuki, and Honda were changing the landscape with fresh engineering ideas, new materials, and refined production techniques. Within just a few years, Yamaha would unveil its legendary Monoshock, setting a new benchmark for long-travel suspension.

But even before that, in a quiet workshop in Wiltshire, Cheney Engineering had already produced something extraordinary — the Cheney Cantilever Prototype.

A QUESTION RARELY ASKED

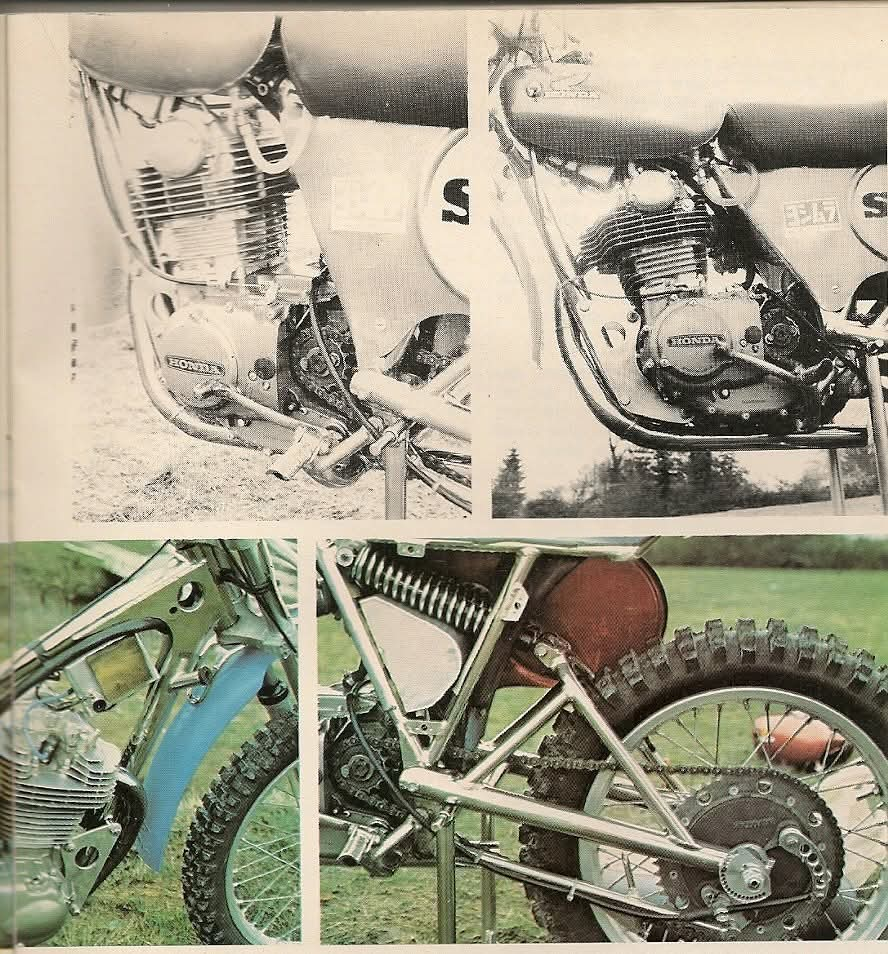

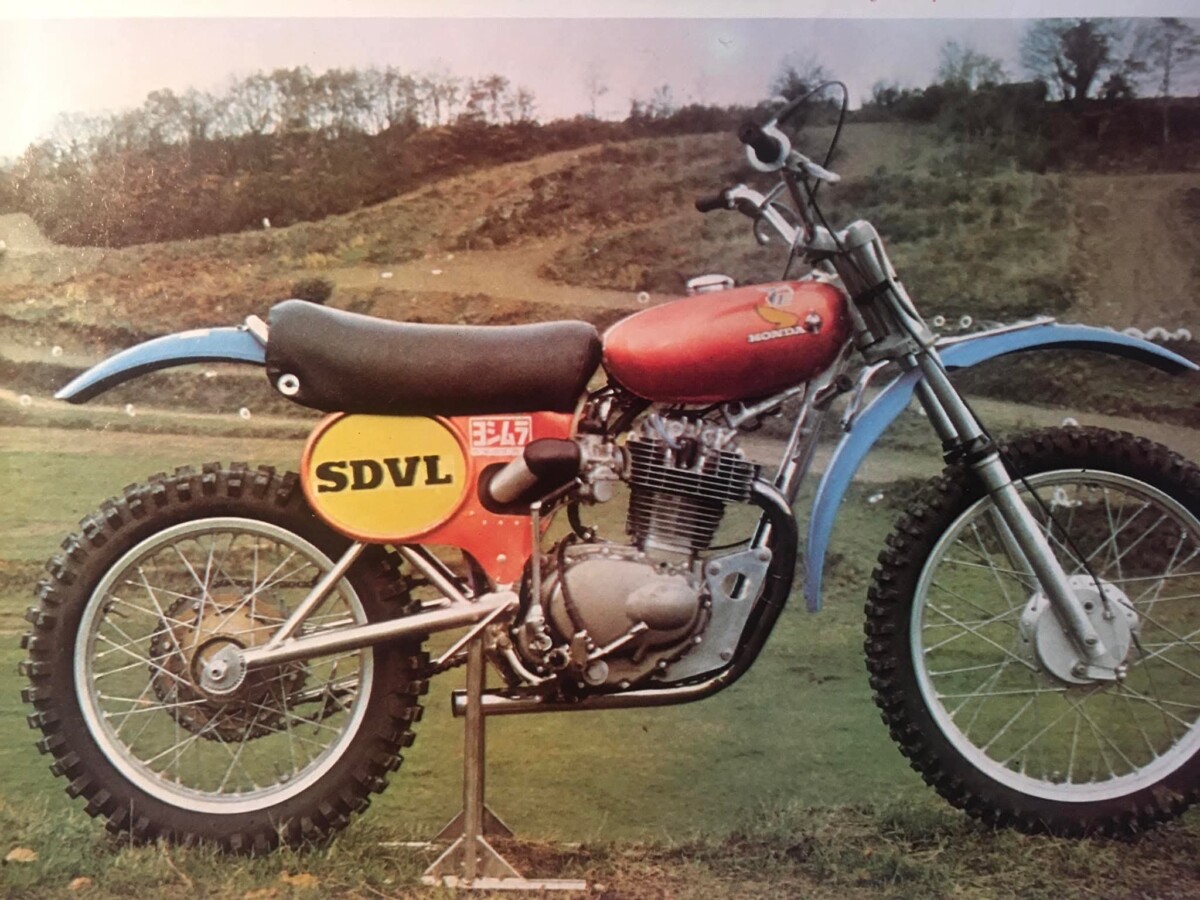

What exactly was the difference between the original Cheney Cantilever prototype and the first twenty frames built for the Honda XL-based version?

The answer comes down to three simple but significant changes:

1️⃣ Engine Mounting:

The Honda engine required its mounting points to be relocated, and the lower frame cradle bars were removed to suit the new configuration.

2️⃣ Shock Mounts:

The front shock lugs were replaced and re-machined to fine-tune the suspension geometry.

3️⃣ The Shocks (the most important change):

The frame design was so far ahead of its time that shock manufacturers simply couldn’t keep up. The cantilever setup created more leverage and wheel travel than existing shock technology could handle. In fact, suspension development lagged 12 to 18 months behind what Eric Cheney’s team had already achieved.

This is one of the main reasons the Cheney Cantilever is often dated between 1973 and 1975 — the frame existed before the right suspension components were available.

HOW IT NEARLY NEVER HAPPENED

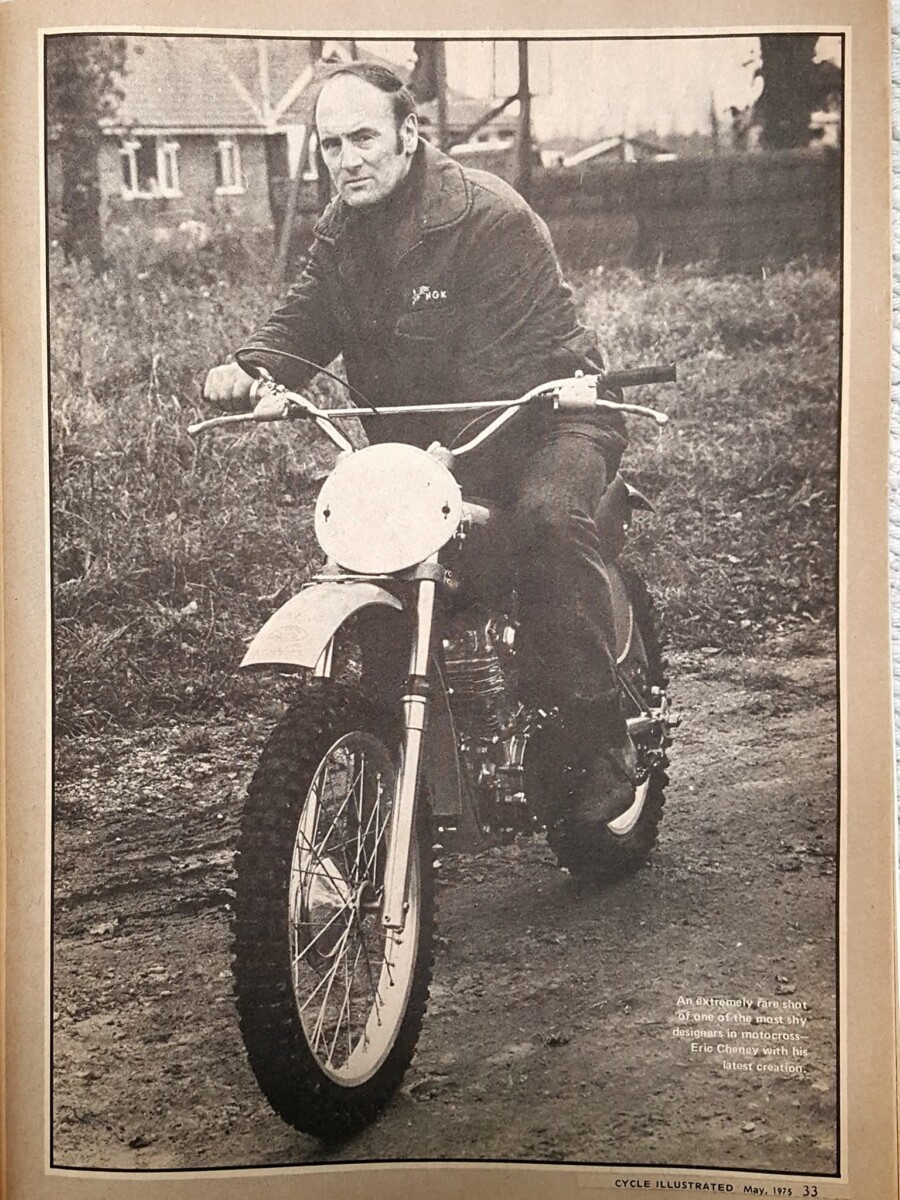

From what I’ve gathered over the years, when the prototype was first shown to Eric Cheney, he wasn’t immediately impressed. At the time, his main focus was John Banks’ world championship campaign, and the cantilever project was quietly set aside. It might have ended there — if not for a fortunate twist of events.

Girling of Birmingham, who were developing new gas-and-oil shocks, handed Cheney a few experimental sets to test. The engineer behind the cantilever concept suggested trying them on his prototype frame. The difference was immediate and dramatic. The bike’s suspension performance transformed — smoother travel, improved traction, and stability well ahead of its time.

That single test proved the design’s worth, and as they say, history began to unfold.

THE HIDDEN CHALLENGE — DRIVE LINE STRESS

There’s one technical issue that often gets overlooked when talking about these pioneering long-travel designs. The added suspension movement placed far more strain on the drive line, particularly the front sprocket and gearbox output shaft.

With the longer swingarm arc, the chain had to be run much looser to avoid binding under full compression. This extra slack caused higher impact loads on the transmission.

To manage it, builders began using chain tensioners, guides, and cush-drive hubs to absorb the shock loads and reduce wear. These small but vital adaptations show how quickly frame innovation was forcing the rest of the motorcycle to evolve alongside it.

On my own Cheney Cantilever, these drive-line refinements were carried out after purchase by my late father, David Watson, whose mechanical skill and eye for detail brought the bike up to an incredibly refined standard. The engine tuning, cush-drive installation, and chain tensioner system were his additions, while the suspension modifications had already been completed by Cheney Engineering at the time of purchase.

Together, these refinements transformed the prototype into a fully sorted machine — powerful, balanced, and durable enough to show what the original design had truly been capable of.

LEGACY

Only a limited number of Cheney Cantilever frames were ever produced, but their influence was immense. They proved that British engineers were already exploring cantilever suspension concepts long before such ideas reached mass production.

When Yamaha and other Japanese manufacturers later introduced their own long-travel systems, they were effectively refining ideas that had already been tested in Britain.

The Cheney Cantilever remains proof that British engineering had outpaced available component technology — and that true innovation often starts in small workshops with big ideas.

PERSONAL NOTE & DISCLAIMER

This article is based entirely on my own research, ownership experience, and investigation, spanning more than five decades with my Cheney Cantilever.

The information comes from conversations (including one with Simon Cheney around thirty years ago), technical notes, magazine articles, and my own mechanical observations over the years.

It’s not an official record from Cheney Engineering — simply my personal contribution to preserving an important, and often overlooked, chapter in motocross history. One of the most advanced and underrated pieces of engineering to come out of the early 1970s — in my opinion 👍

Written and researched by Graham Watson.

More from Graham Watson

The Cheney Cantilever Prototype: Ahead of its Time 🏁 - Editor’s Note: In 2021, we showcased the 1964 Cheney / Triumph “Cantilever Cub” of Graham Watson, whose father built the four-stroke race bike in the 1970s for 12-year-old Graham to compete against racers on non-British […]

The Cheney Cantilever Prototype: Ahead of its Time 🏁 - Editor’s Note: In 2021, we showcased the 1964 Cheney / Triumph “Cantilever Cub” of Graham Watson, whose father built the four-stroke race bike in the 1970s for 12-year-old Graham to compete against racers on non-British […] Race Report: Helsington Classic Scramble 2023 - Graham Watson follows his father’s tire tracks at the 2023 Helsington Scramble! Back in 2021, we featured the unique Cheney / Triumph “Cantilever Cub” of Graham Watson. In the 1970s, Graham’s father wanted to build […]

Race Report: Helsington Classic Scramble 2023 - Graham Watson follows his father’s tire tracks at the 2023 Helsington Scramble! Back in 2021, we featured the unique Cheney / Triumph “Cantilever Cub” of Graham Watson. In the 1970s, Graham’s father wanted to build […] Pure Nostalgia: Cheney / Triumph Tiger Cub - Best of British: Cheney / Triumph Tiger Cub built to battle the two-strokes… If you dig very far into the history of motocross and scrambles, you’re sure to come across the name Eric Cheney, an […]

Pure Nostalgia: Cheney / Triumph Tiger Cub - Best of British: Cheney / Triumph Tiger Cub built to battle the two-strokes… If you dig very far into the history of motocross and scrambles, you’re sure to come across the name Eric Cheney, an […]